Missiles and misinformation: false claims about the India-Pakistan clashes reach millions on X

10 June

On 7 May, the Indian armed forces began Operation Sindoor – a response to a terrorist attack in April which New Delhi blamed on Pakistan. The resulting conflict, involving missile strikes, drone attacks and downed aircraft, lasted until a ceasefire on 11 May. This incident offers a case study of crisis-related disinformation and the limitations of current content moderation approaches.

ISD identified false claims which had received millions of views without any moderation, sometimes using AI-generated content or misleading images; some successfully crossed into national news media, effectively creating a reinforcing cycle. This Dispatch explores the deceptive techniques used to promote false information in a critical moment for national security and offers recommendations for improving current approaches to limiting its spread.

Key findings

- Posts making false claims about attacks on both India and Pakistan spread unchecked on X (formerly Twitter), reaching millions of views. A single claim that Karachi port had been destroyed received 2M views over a week and still has not received a Community Note.

- Actors used a variety of deceptive tactics to support fabricated claims, including using old and unrelated video footage, posting AI-generated content of senior political or military figures, and the apparent hacking of a Pakistani government account.

- The response from social media platforms was inadequate. Users often turned to X’s platform features to verify information. False claims were not consistently annotated by Community Notes and Grok, X’s generative AI chatbot, proved unable to keep up with the rapidly changing information environment, with verification of some claims happening days after they were initially made.

- The conflict shows the importance of platform crisis protocols that ensure users are provided with verified, credible information in critical moments. These protocols should include surge capacity during high-risk events, improved coordination with authorities, and a balance between swift action and human rights safeguards. This likely means limiting the spread of hateful and provably false content and temporary demonetisation to reduce the financial incentive to exploit a crisis.

Methodology

ISD analysed false claims circulating on X from 6 May 2025 when India’s Operation Sindoor began until 11 May, the day after a ceasefire was announced (UK time zones were used for convenience of analysis). False claims were identified qualitatively, based on verified media reporting, official government statements, and (where relevant) Community Notes.

Social media monitoring tool Brandwatch was then used to collect and analyse examples of these claims on X, identify those with the highest levels of engagement, and surface the deceptive tactics that had allowed them to reach large audience.

Use of decontextualised footage

The misattribution of decontextualised footage (typically taken from older or unrelated conflicts/emergencies) is a common deceptive tactic. ISD’s previous research has shown that this is a common issue during crises and is often employed to make events on the ground appear worse, to promote fraudulent claims, or simply because there is limited actual footage. Recent examples include imagery posted during the Iranian missile launches against Israel in April 2024 and during Hurricanes Helene and Milton in October last year.

Image 1. A decontextualised image of a crashed Indian jet which crashed in 2024, and is not a Rafale. A Community Note is displayed underneath; as of 27 May, however, this Community Note no longer exists.

Images that were shared widely on social media during the recent India-Pakistan clashes included photos of an Indian Air Force MiG-29 which was erroneously described as a Rafale that had recently crashed. The post above was made on 6 May by a self-described independent Pakistani journalist claimed that the photo showed a recent incident, despite the image being from 2024. It received 611.3k views and 7.7k likes. In apparent response to criticism that the image was unrelated to the conflict, the same account posted just over half an hour later that the image was used for “illustrative” purposes.

The image was also circulated internationally; it was posted alongside a similar claim by an account seemingly based in the UK on 6 May, garnering over 210k views. A post by a Pakistani “psy-war” account on the same day received 305.6k views and 1.5k likes and featured a different but still decontextualised image of a crashed Indian jet, which it again falsely claimed was a Rafale.

Some popular posts even repurposed imagery from other conflicts, for example one from 7 May featured a Hindu deity superimposed over the supposedly burning skyline of the Pakistani city of Sialkot, which was actually taken from Gaza in 2021.

Image 2. Another decontextualised image of an Indian jet which is not a Rafale and crashed in 2021.

While many of these posts came from regular X users without government affiliation, a striking example of misattributed footage came from an official Pakistani government account. On 8 May, the account posted a video montage featuring a clip from the video game Arma III. The post, which threatened a “befitting reply” to India’s operation, has been viewed 2.4M times. This raises questions about the use of social media platforms by government entities and their communications responsibilities during critical moments for national security.

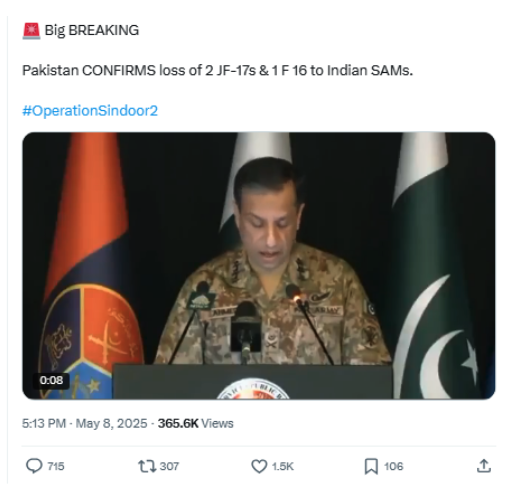

Unrelated and misattributed footage is often used to add credence to existing false claims. For example, on 8 May a Hindu nationalist account declared that the “entire port [of Karachi] is in ashes” at around 6:30 PM BST; over the course of the next four days this post accrued 2M views and 60k likes. Other accounts on X sought to add legitimacy to this claim using misattributed media: one posted footage from the January 2025 Philadelphia plane crash, receiving 2.9M views and 23k likes. Other images posted to reinforce the claim about Karachi port included stock photos of INS Vikrant firing a missile from an old press release: one such post received 511.8k views and 1.7k likes.

Image 3. Examples of false claims about the destruction of Karachi Port, both which claim that Indian aircraft carrier INS Vikrant had been involved in an attack.

This content has implications beyond social media. In the case of the Karachi port, ISD identified at least 10 Indian news channels which claimed that the port had been attacked off the basis of these widespread claims on social media. This situation was further exacerbated on 9 May, when the port’s official account posted that it had “sustained heavy damage following a strike by India” – Karachi port alleges this was the result of an account-level hack. A more substantial and sweeping response to false claims by social media platforms could have mitigated some of this fallout.

AI-generated content (AIGC)

AI-generated content (AIGC) includes media (typically video or audio) which have been digitally manipulated to change what is said or shown. Previous research from ISD has noted the proliferation of AIGC across a variety of political contexts, including in the German and US elections, with the intent of blurring the truth.

Perhaps the most impactful piece of AIGC circulated during the recent conflict between India and Pakistan used doctored audio and a video of Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry, Director General of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Public Relations. Chaudhry appeared as a key spokesperson for the Pakistani military during the conflict, providing updates on the situation. An altered video of him (based on footage from 2024) first emerged on 8 May; in the clip, he claims that two Pakistani JF 17 jets were shot down by Indian forces. The video has been confirmed as AIGC by OSINT analysts.

X’s content policies ban the sharing of “Synthetic and Manipulated media…that may result in widespread confusion on public issues”. However, ISD was able to identify a number of accounts featuring synthetic media that garnered significant engagement during the conflict: the most successful had 824.8k views and 1.3k likes as of 14 May, while the second most popular had 365k views and 1.5k likes. Both posts came from verified accounts.

Image 4. An AIGC video in which a senior Pakistani official says that India had downed Pakistani aircraft.

By contrast, an AIGC video of US President Donald Trump expressing support for India received significantly more Community Notes. In the manipulated clip, which was released shortly before the start of Operation Sindoor, Trump threatens to “erase Pakistan” if it attacks India. A clip posted on 1 May received 793.3k views and 13k likes; however, it received a Community Note within less than 24 hours; all identical clips also featured a tag denoting it as “manipulated media”, regardless of size.

The inconsistent approach to manipulated media may reflect the fact that Chaudhry has a significantly lower profile figure than Trump, potentially making it harder for accounts to definitively conclude that the video is AIGC and for AI detection tools to evaluate with high certainty that the video has been manipulated. It underlines the importance of AIGC detection in crisis periods, with a focus on actors in the conflict zone as well as international figures.

Community Notes

Community Notes, typically short rebuttals of misleading claims with links to factual information, were deployed across X in 2023. Previous research from Full Fact found serious issues in Community Notes, including inconsistent application and an inability to meet time sensitive political situations.

Our research supports this finding, with the efficacy of Community Notes proving to be inconsistent and ineffective in a rapidly-changing conflict situation. For example, the first decontextualised image of crashed Indian aircraft (labelled as Image 1) received a Community Note within 10 minutes; in response, the original account claimed that the image was “illustrative” 30 minutes after the Community Note was added. However, as of 27 May, the Community Note has been removed with no indication or explanation.

Image 2 (with a similar decontextualised use of a crashed aircraft) received no Community Note at all; neither did the two posts featuring AIGC videos of the Pakistani official (Image 4). In other cases, there was a significant delay between a post being made and a Community Note being applied. For example, the Community Note related to the misleading post from the account belonging to the Government of Pakistan was only posted more than 20 hours later.

Even within the same claims, ISD found that Community Notes were highly inconsistent. For example, the original post about Karachi port being destroyed received no Community Note despite receiving 2M views, as did a post including stock footage of Indian aircraft carrier INS Vikrant (Image 3). However, the post featuring decontextualised footage from the January 2025 Philadelphia plane crash received a Community Note within 40 minutes of the original post.

The shortcomings of Community Notes in this case in part stem from the limited clarity and at times conflicting information provided by government spokespeople during the conflict (discrepancies in official claims about the number of aircraft lost by each side persist, for example). The highly partisan nature of this crisis thus differentiates it from incidents that have produced ‘information voids’, such as the Southport attack. However, the examples provided above were disproven by trusted independent sources yet still received inconsistent Community Notes.

This is significant given the direction taken by major platforms in shifting the responsibility for combating misinformation from themselves to their users. X removed labels such as “state-affiliated” in 2023, making it harder for users to understand quickly whether a news source is linked to a specific state actor and therefore is likely to have a bias in reporting. In January 2025, Meta announced it was planning to move away from utilising third-party fact checking partners within moderation systems and instead rely on a user-driven approach to verifying the veracity of information.

An additional development during the conflict was frequent usage of Grok, X’s AI chatbot, to check whether claims were real or not. The role of AI in fact-checking is challenging given that the large language models (LLMs) responses rely on accurate an timely training data and often suffer from hallucinations, providing fictionalised content. The highly contentious nature of the conflict and the persistent “fog of war” also limited Grok’s ability to provide clarity, noting in one case that “both sides’ conflicting narratives make the situation complex.” Contentious and partisan claims – for example, about the number of Indian jets which were downed during the fighting – are challenging to fact-check: India only confirmed that it had lost fighter jets in June, almost a month after the fighting commenced.

Recommendations

These examples of deceptive tactics reflect the challenges of social media content in conflicts; they also expose the limitations of platform policies. While online crisis protocols already exist to combat the spread of violent extremist content online, a comparative system is lacking for crises.

Effecting such measures is particularly urgent for platforms in jurisdictions such as the EU: Under the bloc’s Digital Services Act (DSA) and additional guidance from the European Commission, social media platforms will be required to address widespread threats to civic discourse stemming from their services.

The measures necessary for such a crisis protocol include:

- Surge capacity during high-risk events, with a focus on personnel with knowledge of geopolitical nuances and relevant languages,

- Real-time monitoring of events and escalation channels for false claims which do go viral, with the aim of limiting their spread into the news cycle,

- Improved coordination with authorities and an awareness of how governments may be unwilling to provide clarity during ongoing military operations,

- A balance between swift action and human rights safeguards,

- Limiting the spread of hateful and provably false content, particularly from accounts which are being algorithmically boosted (e.g. verified users on X)

- Demonetising actors known to produce false and misleading content to reduce the financial incentive.

Conclusion

That India and Pakistan have reached a ceasefire is heartening, even if peace remains fragile between the neighbours. Nevertheless, this analysis shows that platforms are ill-prepared to deal with the proliferation of misinformation during international conflicts. This carries significant risk of real-world consequences, especially when news media disseminates false claims: it can undermine efforts towards de-escalation, driving policy decisions or legitimising actions by non-state actors.

The recommendations outlined above provide some ways to mitigate these challenges in future conflicts. Fundamental to them is the understanding that deceptive tactics during crises require immediate and consistent responses. Failure to implement stronger policies risks further offline violence and escalation in the future.